Walk into a coffee shop, and chances are you’ll stumble upon a book club in full swing. A group of people (most likely women) huddled together (most likely in a circle) debating the nuances of a chosen novel while sipping coffee or swirling stems of wine. Whether you’ve succumbed to the allure of a book club yet or not, they seem to be everywhere.

I, too, am a member of a book club. A couple of years ago, some girlfriends and I found ourselves engaged in conversation at a holiday party, all of us sharing a common goal: to read more. And just like that, our book club was born. It’s grown since then, and while we don’t always meet when we say we will, we’ve managed to keep it going for four years.

Chances are, you’re like my friends and me, either part of a book club or itching to join one. It’s hard to pin down exactly how many book clubs are out there. The only number I could find was a conservative estimate from almost a decade ago, which put the total number of book clubs in the United States at 5 million. I’d wager it’s safe to say that number has more than doubled by now. Digital book circle Goodreads boasts over 150 million members alone. Clubs range in style from intimate get-togethers hosted in homes, at libraries and coffee shops to colossal digital social media circles run by celebrity curators. Oprah Winfrey and Reese Witherspoon are two of the biggest names in the game. It seems like everyone, from singers and actors to influencers, is getting in on the action.

Which got me thinking: where did the rise in book clubs come from? And why does it seem the majority of book club members are women? Is there a correlation here?

So I went digging.

The Anatomy of a Book Club

Before we dive into the history of book clubs, let’s break down the essential elements that define a book club. Every thriving book club shares a similar set of basic characteristics:

- A common piece of literature — The heart of any book club, this is what brings people together.

- Members — A diverse group of individuals, each bringing their own unique perspectives.

- Communal gathering space — Whether it’s a cozy living room, a local coffee shop, or a virtual meeting room, it’s where members meet.

- Discussion and sharing of ideas — The lifeblood of the book club, where thoughts and interpretations freely flow.

- Refreshments — While not required, they are greatly preferred (because let’s face it, everything’s better with snacks).

This combination of traits is what sets a book club apart from, say, a lecture, where one person is primarily educating a group on a topic and sharing a single perspective. It’s the unfiltered improvisation of the group’s combined perspectives that really drives the conversation forward.

A Timeline History of the Book Club

To really get to the root of the book club, we need to start with the ancients.

One could argue that book clubs have been around in some form since prehistoric times when humans told stories, shared knowledge, and communicated ideas orally. They gathered around fires in communal spaces to tell tales, myths, and spread important survival information, such as hunting techniques and medicinal plant knowledge. It wasn’t until 3200 BC in Mesopotamia (current-day Iraq) that the first written language made its appearance in the form of cuneiform. Soon after, civilizations from Egypt to Greece and Rome had their own forms of written language combined with oral tradition, which served not only as entertainment but also as a means of preserving cultural values and history.

In 400 BC, Greek philosopher Socrates formed Socratic Seminars, a.k.a. Socratic Circles, to combat the common lecture-style of learning where teachers used rhetoric to entertain, impress, and persuade a person of their point of view. In contrast, Socrates encouraged a spreading of ideas through group discussion using open-ended questions that encouraged lively discussion. In Socratic Seminars, gaining insight into a particular text was more important than answering questions “correctly.” These seminars starkly resemble the structure of our modern-day book clubs: a group of people meeting to discuss a text or idea and explore questions of human nature, politics, life, and reality.

Fast forward a couple of hundred years, and we find ourselves in the Medieval Dark Ages, a time named for its lack of written historical records and a supposed period of decline in culture and sciences. But the dark ages weren’t as dark as we’re led to believe. During this time, bards and troubadours traveled from place to place holding oral performances at feasts and jovial gatherings, reciting poetry and telling stories that relayed culture and historical events. In a time without television, radio, books, or newspapers, bards were rich sources of information and entertainment, receiving enthusiastic invites from townsfolk, lords, and kings alike. Bards weren’t exclusive to Anglo-Saxon territories; variations of bards are found in countries all over the world, such as in Western Africa, where they were known as Griots.

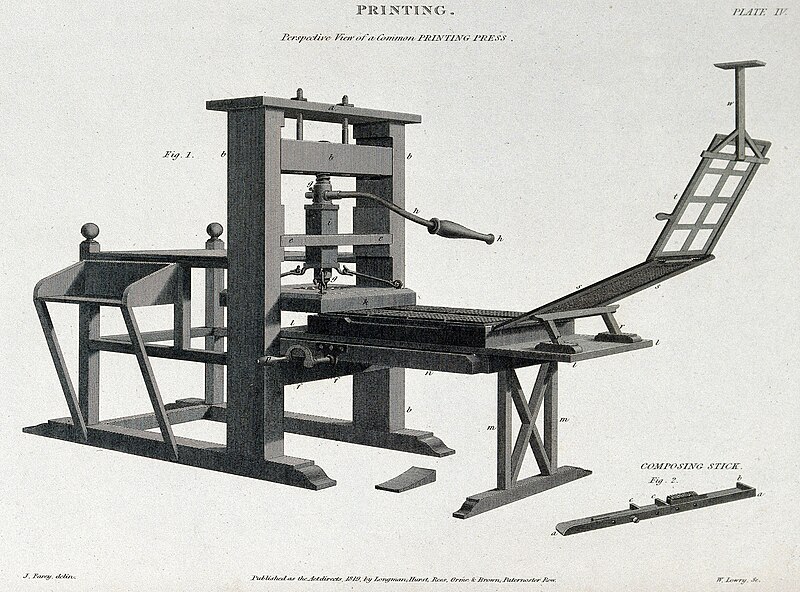

In the 1400s, the western world crawled its way out of the Dark Ages, much thanks to the advent of the printing press around 1440, which soon ushered in the age of The Renaissance, a time rich in the spread of art, politics, science, literature, and the all-around expansion of culture and ideas.

I can’t understate the influence that the printing press and the mass production of information had on society in the democratization of knowledge and the circulation of ideas. Never before could ideas be so quickly documented, produced, and distributed throughout communities. By the end of the 15th century, the entire classical canon was printed and distributed throughout Europe. Along with it, the adult literacy rate skyrocketed, and more people could now discuss these works, both old and new. Newspapers, bulletins, books, and pamphlets were pivotal for monarchies in rallying support from the populace for their various causes. But they also equipped members of the opposition to do the same thing, which led to issues around censorship and freedom of the press. The printing press also received criticism for creating and disseminating incorrect information — the first instances of fake news, if you will.

Colonial Expansion & the Expansion of Literature — From Salons to Societies

As we moved into the 1600s, the printing press made it easier to produce literature, but books were still a luxury. Despite the rapid spread of ideas and knowledge following the printing press, the average person struggled to get their hands on a book of their own. At its advent, a Gutenberg Bible cost three to four years’ worth of common labor wages. Enter the rise of European salons and coffeehouses. These communal spaces hosted social gatherings where people from all backgrounds — from townsfolk to writers, scientists, and philosophers — gathered to discuss literature, politics, and ideas. These spaces were havens that encouraged sociability, equality, and communication. However, there was one significant distinction between coffeehouses and salons: while men were welcome at public coffeehouses, women were either not permitted or largely unwelcome unless they were there to “work” (if you catch my drift). Private salons provided the refuge women needed, as women were the leaders and owners of salons and had the power to grant entry to whomever they saw fit—typically other women looking for a communal space to discuss ideas.

In 1634, we see the first recorded instance of an actual book club as we know it today. A woman by the name of Anne Hutchinson launched a scripture reading circle for other women during her voyage from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony to discuss the Bible and the week’s sermons. Upon arriving in the colonies, her club continued, but when it became more popular than the official local church service, she was exiled from the colony completely.

Pay attention to this theme, as it will recur throughout history and very well plays into why book clubs have disproportionately attracted women members. Anne Hutchinson’s book/sermon club inaugurated a tradition of women’s analytical discussion of serious texts during a time when women’s opinions didn’t matter. Throughout the coming centuries, there’s a cycle of women’s enlightenment, a ban or critique of said enlightenment, and ultimately a downfall, only to encourage women to come together to discuss women’s ideas once again.

During the following decades, the price of books decreased, only serving to increase the general public’s demand. And as more books appeared, people invented new ways to access them. City libraries in Europe opened, shortly followed by libraries in America, many of which required a fee to join. It was Benjamin Franklin, along with members of his own book club, the Junto Club, and the Library Company, who placed the first book order to London in 1732 and brought membership libraries to the Americas. While they weren’t all fully public at this point, class access grew across class lines, fueling the trend for demand and growing literacy rates.

Now, when you hear the word “library,” you probably envision a hushed hall of somber people amid rows of book stacks. During the 1700s, this wasn’t the case. Libraries were places to find books as well as social institutions in themselves. One popular library had a billiard room, a public exhibition room, and a music library. “They were not the hushed environments that we now associated with libraries, but, at their best, elegant spaces full of people to converse with,” Abigail Williams writes in The Social Life of Books.

Libraries were actually a bit controversial as they blended class lines by giving more than elite circles access to books and also offered women a place to congregate outside the home.

The growth of book clubs directly paralleled the rise of libraries. By the end of the 18th century, over 1,000 private book clubs met in the coffeehouses, inns, salons, and homes of New Englanders. They all carried themes of discussing literature, culture, politics, philosophy, and gossip. But it was the key feature of dinners, drinking, and camaraderie that distinguished them from other libraries and membership societies.

In book clubs today, every member may buy or procure their own copy of the book, but in the 18th century, when books cost a pretty penny, books were shared and often read aloud at meetings. And part of the point of a book club was to pool resources to buy more books, whose access contributed to their appeal among members.

The mood of these early book clubs was well summarized in a poem in 1788 by Charles Shillito, who wrote a satirical poem depicting The Country-Book Club:`

Thus, meeting to dispute, to fight, to plead,

To smoke, to drink—do anything but read —

The club—with stagg’ring steps, yet light of heart,

Their taste for learning shown, and punch — depart.

I highly recommend reading the poem in full with its talk about leaving behind the pain of the plough to enjoy homemade wine, beer and discussion at the hearth among friends.

Book Clubs of the 19th Century — Catalysts for Change

The 19th century marked a pivotal era for book clubs, transforming them into powerful agents of change in society, particularly in advancing liberation movements for women, races, and social classes. While white men had long convened in exclusive groups and secretive societies, it was now time for other Americans to demand the same rights as well.

1821 the first reading circle for black men was established, and just six years later, in 1827, black women founded the Society of Young Ladies in Massachusetts “to meet once a week, to read in turn to the society, works adapted to virtuous and literary improvement.”

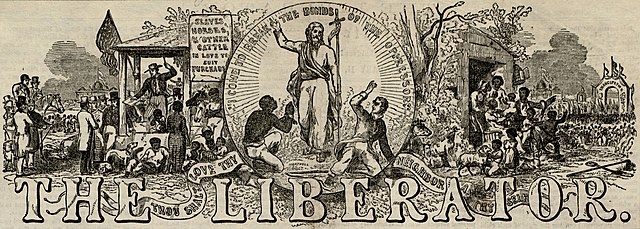

A young black feminist and abolitionist named Sarah Mapps Douglas co-founded the Female Literary Association in 1831. At the age of 25, Douglas and the members would gather every Tuesday evening “for the purpose of mutual improvement in moral and literary pursuits.” They would write original pieces anonymously that would then be discussed and critiqued by the members. They found an unlikely ally in a white, male abolitionist and founder of The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison, who praised the group, stating, “If the traducers of the colored race could be acquainted with the moral worth, just refinement and large intelligence of this association their mouths would hereafter be dumb.” Garrison proceeded to publish their writings in The Liberator, not only for their merit but to encourage women of color in other regions to follow suit. Douglas saw it as their duty as women and African Americans to use their talents to break down the existing divides between African Americans and Whites and to fight for equal rights for people of color.

The founding of these abolitionist clubs ushered women deeper into the fray. Women began using their leisure time to meet in “Culture Clubs” for the sole purpose of literary endeavors, history, culture expanding their knowledge, creating social opportunities for white middle-class women, and questioning their purpose in life. The growth of these ideas often developed into practical action, and women became involved in anti-slavery groups, temperance groups, and women’s suffrage organizations starting in the 1840s. The important work they were doing showed that women deserved a spot in the world of big ideas.

Two prominent book clubs formed during this time. Sorosis was founded in 1868 after women journalists were excluded from an all-male New York Press Club event where Charles Dickens was speaking. The club had 83 members by the end of its first year and went on to inspire similar clubs throughout the country. Another book club, Conversations, was founded by prominent journalist Margaret Fuller in 1893. Women would openly ask one another, “What were we born to do? How shall we do it?” while comparing their educational prospects to those of the men they knew.

It’s important to note that book groups didn’t all necessarily look alike. Middle-aged women married to middle- and upper-class men had the most time and freedom to enjoy book clubs, as well as money to spend on books, but working-class women made their own circles as well. One group of millworkers short on leisure time made time to discuss literature while they worked.

All these book clubs had one thing in common: to develop the minds of the members and their communities. They debated everything from the merits of studying the natural sciences versus art to whether or not Socrates was justified in his suicide. No topic was “deemed too much,” including discussions around white privilege (“Which has the white man most injured, the Indian or the African?” was the topic of one 19th-century meeting), politics, economics, and, of course, gender roles. But it wasn’t just talk. They were all engaged in “critical thought, civic discourse, and cultural production.” Book clubs ran literary magazines, built libraries, and sponsored speaking groups. Once universities began allowing women to study, book clubs funded scholarships and established trade schools for women. Members advocated for the integration of kindergarten into the public school system and even ran them until the state would step in.

The Modern Revitalization of the Book Club

And the trend continued into the turn of the century, with book clubs continuing to serve as both an intellectual outlet and a radical political tool. Literary greats such as Virginia Woolf, J.R.R. Tolkien, Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway were all members of book clubs.

One of the biggest contributors to the modern mass adoption of book clubs was the first monthly book club delivery in 1927. Harry Sherman’s Book of the Month Club had some 60,000 subscribers who paid for monthly delivery of current books. Titles included Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, and Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird. The club encouraged average Americans to take on hefty literary novels.

Then in the 1960s and 70s, women experienced a second wave of feminism as they began to attend higher education en masse. Women sought communities to better both themselves and their communities, which was the impetus behind the consciousness-raising (“CR”) groups that were foundational to the women’s movement of the 1960s and the ’70s. These smaller meetings more closely resemble today’s book clubs than the women’s clubs of the 1800s. CR meetings united women so they could discuss how sexism had affected them personally and how they might inspire change. Radical feminists wanted to move away from the legal focus of their suffragist foremothers. Instead of creating a revolution that advocated for more rights within a patriarchal system, researcher Alice Home notes CR groups focused more on self-help and promoted “greater self-confidence, self-acceptance, self-awareness, and feelings of more independence.”

But book clubs still weren’t modern in the sense as we know them today. That happened in 1984 with the modern book club boom that has yet to stall. It’s thanks to the 1984 novel And Ladies of the Club that told the story of a longstanding book club. Santmyer’s novel inspired the formation of book groups across the country and became a national best-seller, inspiring others to form their own clubs.

Then in 1996, Oprah launched her book club, which threw gas on an already burning fire. The Oprah Book Club sent the explosion of book clubs into hyperdrive. According to Oprah, books have “lessons,” the novels’ characters are potential “friends,” and reading is a transformational act.

While celebrity endorsement contributed to the rise of book clubs, it also contributed to clubs being seen as “middle-brow culture.” Remember that cycle I told you to pay attention to? Here it is in all its form.

Author Jonathan Franzen famously expressed this sentiment when, after the Oprah Book Club chose his novel The Corrections in 2001, he referred to her previous picks as “schmaltzy” and “one-dimensional.” Franzen also had negative things to say about seeing a corporate logo on his book cover. This debate embodied the discomfort writers and academics had with Oprah’s Book Club, which came to represent the commodification of literature and the lowering of literary standards.

While the more intellectual among us might call the Oprah Book Club middle-brow and lament its departure from intellectual beginnings, this sentiment is nothing new. Book clubs have a history of being dismissed as a place of gossip and frivolity going back to the 1700s.

I don’t know about your book club, but in mine, we read and discuss a mixture of summer pool reads as well as thought-provoking stories of political and current events. That’s the beauty of the book club; it doesn’t need to be one or the other. Book clubs are a haven to escape the daily responsibilities of life, be in community, drink, gossip, have a nice evening, to share ideas and have them matter. Perhaps you discuss the book. Perhaps you don’t. The book is the excuse, not necessarily the point.

And, just as the first wavers’ clubs allowed women to view themselves as intellectuals, book clubs permit the women os today to view our personal experiences as significant and worthy of sharing.