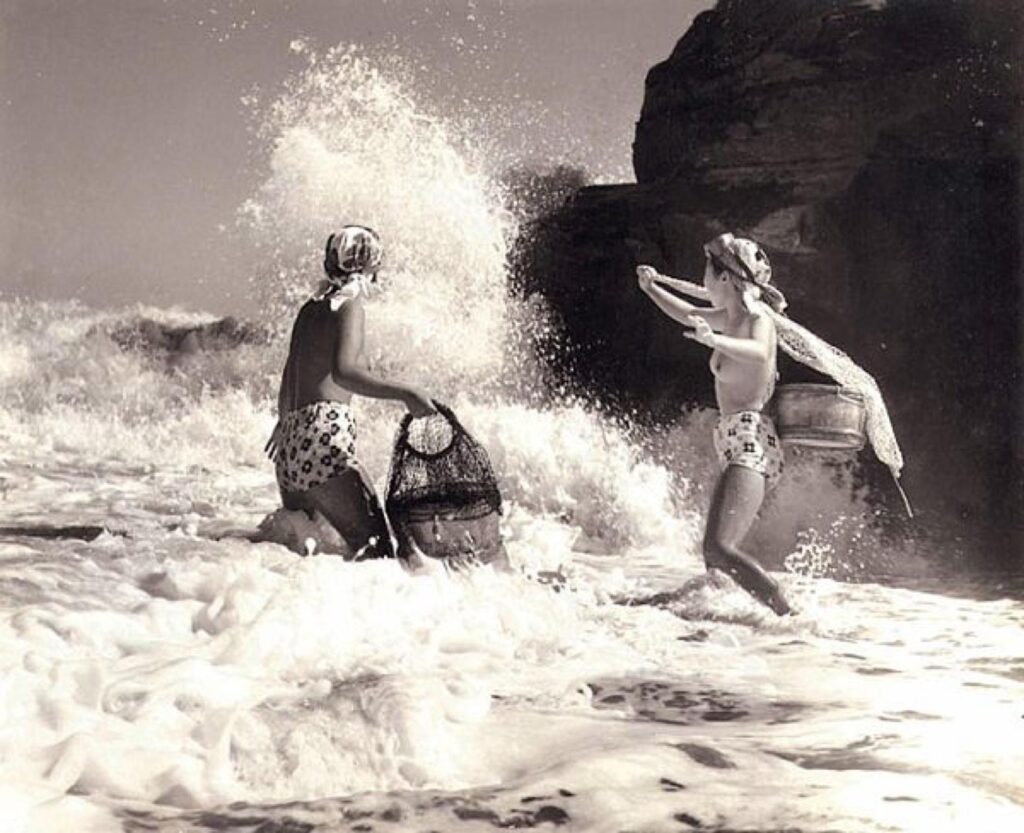

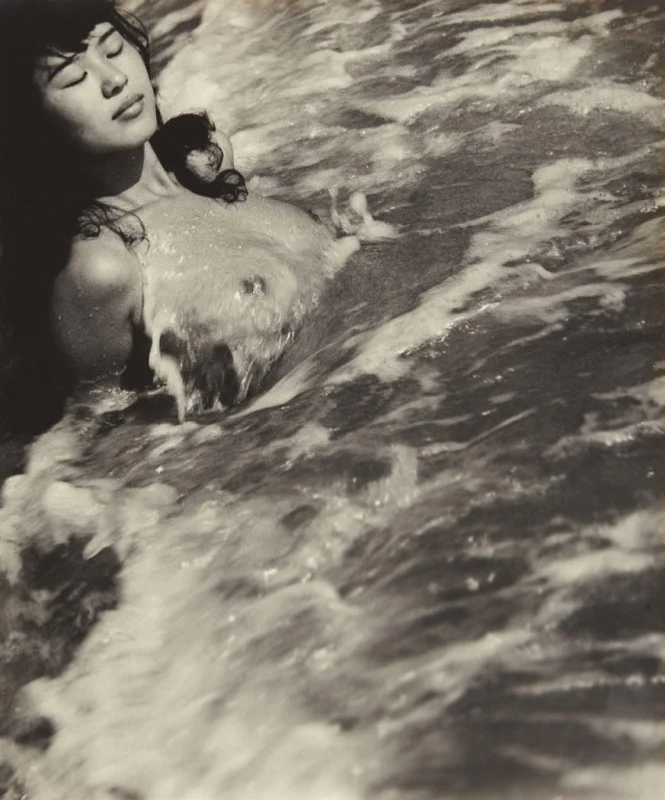

In a small coastal village in Japan, a woman pulls on her white diving garb. She’s 78 years old. Her toes are weathered from decades of salt water, sun and gripping slick ocean rock. She carefully picks her way across the stony shore carrying her diving gear. But she doesn’t wear an oxygen tank, nor does she carry a spear. She slips into the sea with nothing but her breath—and the knowing.

This is an Ama, a sea woman.

For over 2,000 years, Japan’s Ama divers have made their living free-diving into cold coastal waters, harvesting abalone, sea urchin, shellfish, sea cucumbers, and seaweed. At their peak in the 1960s, there were over 30,000 Ama women. Today, fewer than 2,000 remain—and most are grandmothers.

But don’t let their age fool you, these women are tough.

Ama have learned to hold their breath for over two minutes, dive more than 60 feet down, and return with arms full of ocean offerings. And when they come up, they release a sound called the isobue—a sharp whistle, half birdcall, half spell. It’s how they let the others know:

I’m okay. I’m still here.

A Culture Born of Water

The word Ama means “sea woman.”

Not “sea girl.” Not “sea wife.”

Woman.

Being an Ama is a matriarchal tradition, passed down through generations of coastal Japanese families. In many villages, diving is the primary source of income—and the women, not the men, are the breadwinners.

Men fish on boats. Women dive.

There’s a balance in that. A rhythm between sea and shore, marriage and solitude, breath and plunge.

Aspiring young Ama don’t dive right away. First, they watch from the rocks—small, barefoot, silent—studying the tides and the way their predecessors move through the water. They learn to read the ocean before they ever enter it.

Then comes the wading. The shallow collecting. The breathwork. Training isn’t formal—it’s absorbed, like salt into skin. A girl might spend years learning how to spot abalone among the rock and the fundamentals of what it means to be a woman of the sea.

Eventually, she joins the others. Not with ceremony, but with quiet acceptance. You become an Ama when the ocean says you’re ready.

Ama rest in between dives in small beach huts called amagoya. These huts aren’t just for drying off—they’re community spaces. Places for storytelling, fire-building, tea, and laughter. Always laughter.

After all, it’s said the ocean is more generous to those who approach her with joy.

A Life Below the Surface

What makes the Ama so extraordinary isn’t just that they dive. It’s how they do it.

Ama are freedivers, meaning they descend on a single breath to depths over 65 feet (20 meters). They don’t use scuba tanks or breathing equipment. Most carry only what they need: a simple cloth diving outfit or wetsuit depending on the season, a face mask, a weighted belt for control, and a rope-tethered basket to hold their catch.

Some dive barefoot. Others carry small knives tucked into their belts. The tools are practical, unchanged for generations.

Each dive follows a practiced rhythm. Inhale. Dive. Search. Surface. Rest. Then again. And again. On a typical day, an Ama might dive up to over 90 times.

Yet, there’s no rush to it. No sense of competition. The pace is dictated by the sea—and the diver’s breath.

Ama are known for understanding their limits. They don’t force a dive. They read the conditions, respond to shifts in current, and pay attention to what the water allows. That mindset is part of what has kept the tradition alive for so long.

The sea is not a place to conquer, it’s a place to work with. And when treated with patience and respect, it provides.

Sisters in the Sea—Korea’s Haenyeo

Japan’s Ama are not alone.

Across the sea, on Korea’s Jeju Island, another ancient diving tradition endures. The haenyeo—“sea women” in Korean—are also free-diving matriarchs, some well into their 80s. They harvest similar coastal bounty and share the same philosophy of harmony with the ocean, communal support, and intergenerational knowledge.

The Glamour Years

If you’ve heard of the Ama, it’s likely because of the pearls.

The association between Ama divers and pearl cultivation began in the late 19th century, when Kokichi Mikimoto developed the world’s first cultured pearls. To make it possible, he relied on Ama—employing them to collect and tend to the oysters used in his experiments, particularly in the waters around Toba in Mie Prefecture.

As Mikimoto’s pearls gained international acclaim, so too did the image of the Ama. Tourist postcards began to circulate, showing women in revealing suits, hair loose, glistening with saltwater. Western fascination labeled them “mermaids” and “sea nymphs.”

That fascination eventually reached the big screen. In You Only Live Twice (1967), a James Bond film set in Japan, the fictional character Kissy Suzuki is introduced as an Ama diver—mysterious, elegant, and cinematic.

It was a striking image, but it wasn’t the whole story.

The real lives of Ama divers looked very different. Pearl diving was physically demanding, dangerous, and often poorly compensated. The mystique may have been commodified, but the women themselves remained grounded. Resilient. Not symbols. Not fantasies—just women working with the sea.

The Sea Remembers, Even If We Don’t

Today, the Ama are disappearing.

Tourism, pollution, climate change, and changing values have all made the tradition harder to maintain. Coastal villages grow quieter as younger generations leave for the cities. The water gets warmer. The shellfish fewer. And with each passing season, the tides feel a little less predictable.

Overfishing has taken its toll, too. Not just from industrial trawlers, but from decades of human pressure on delicate marine ecosystems. The abalone and sea urchin the Ama once gathered in abundance are now harder to find, and their habitats more fragile.

If you’re curious to understand more about the complex pressures facing our oceans—everything from illegal fishing to climate stress—The Outlaw Ocean by Ian Urbina is essential reading (and listening). It will make you think differently about the sea and everyone who works it. It’s also some of the most gripping journalism in recent memory.

The work is no longer sustainable as a sole source of income. For many, it’s no longer passed down at all.

And yet, some still dive.

Well into their seventies and eighties, they return to the sea. Not for money. Not even strictly for tradition. But because they can’t imagine not diving. Because the ocean is a part of their body now.

The Ama may be fading. But their way of being—quiet, resilient, deeply in rhythm with the ocean—is something the world can still learn from. Before it’s gone.

Further Reading:

- The Last Wave by Andi Cross for Oceanographic

- The Island of Sea Women by Lisa See

- The Mermaid from Jeju by Sumi Hahn

- UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage listing for the Haenyeo